Welcome to the party, Sickos of Summer.

So long as you’re here, go check out The Sickos Sentinel. If you’ve already done that and have come here because you’re a fellow Sicko, hello (it’s specmotors from the Discord) and welcome to you, too! And check out our Discord, because, can you ever really have enough places to post?

Anyway, you were promised a sports rabbit hole yesterday, and it is time to deliver on that promise.

Since we’re not going to see Edwin Díaz pitch again for quite some time (sigh), here’s the list of the most strikeouts in a season, by a pitcher with 3.0 walks per nine innings or fewer, a 2.00 ERA or lower, and an FIP of 1.00 or lower. A list of 3-2-1… K, if you will.

Eric Gagne, 2003 Dodgers, 137

Díaz, last season, 118

Craig Kimbrel, 2012 Atlanta, 116

Sergio Romo, 2011 Giants, 70

Devin Williams, 2020 Brewers, 53

Ed Cushman, 1884 Brewers (Union Association), 47

The 1884 Brewers played 12 games. Cushman pitched four of them, won all four, and gave up a total of four runs, two against the Boston Reds and two against the Baltimore Monumentals (do not get any ideas from this, Ted Leonsis).

Cushman, in his career, pitched for the 1883 Buffalo Bisons in the National League, then had those four starts for Milwaukee the next year, and moved on to the American Association in 1885, pitching for both the Philadelphia A’s and the New York Metropolitans – at the original Polo Grounds, the place that had actually been built for polo in 1876. It was those Metropolitans who converted the field, across the street from the northeast corner of Central Park, into a baseball park.

In 1886, the Mets moved to the St. George Cricket Grounds on Staten Island, and Cushman won a career-high 17 games… while losing 21, those Mets weren’t so good. Cushman was fourth in American Association pitching WAR that season, and ranked seventh in the league at 4.62 strikeouts per nine innings.

Here are the Mets pitchers who had fewer than 4.62 strikeouts per nine innings last season: Nate Fisher (one strikeout in three innings, 3.0 K/9) and Darin Ruf (zero strikeouts in two innings, 0.0). Among regularly-appearing pitchers, Adonis Medina checked in at 6.5 K/9, Taijuan Walker at 7.6, and Chris Bassitt at 8.3. In 1886, the American Association leader was Matt Kilroy of the Baltimore Orioles at 7.9 (513 strikeouts in 583 innings).

Kilroy completed 66 of his 68 starts, just shy of half the Orioles’ 139 games – shoutout to their other two main starters, Jumbo McGinnis and Hardie Henderson. The Orioles were the only team the Mets finished ahead of that year – the St. Louis Browns won the league, then beat the National League champion Chicago White Stockings in the 1880s version of the World Series.

Chicago outhomered St. Louis, 3-2, getting dingers along the way from George Gore, King Kelly, and Fred Pfeffer, but only managed a .195/.254/.300 line against St. Louis pitching in the series. The Browns, led by Canadian legend Tip O’Neill (who really went off the next season) going 8-for-20 with two triples, two homers, and four walks.

Cap Anson was 5-for-21 in the series. He’s the son of a bitch that Shoeless Joe and the rest of the ghosts in Field of Dreams should’ve told to stick it.

Cushman, meanwhile, spent 1888 and 1889 out of Baseball Reference’s data set, but according to Wikipedia playing in Des Moines. When the manager there, Charlie Morton, took the job managing the Toledo Maumees, Cushman returned to the American Association with him.

And no, of course not that Charlie Morton, but the manager of a previous Toledo team, the Blue Stockings, that had Moses Fleetwood Walker and Weldy Walker — and whose presence on that team gave Morton a chance to be someone other than a footnote in the history of racism, as both the manager of the Walker brothers’ team, and the first guy to get steamrolled by Anson’s racism. Morton declined the hero role, although his Wikipedia page (this is already a tangent on a tangent, at least, but important) makes it very clear both that he had the chance and that his motivation was not racism but something even more American, dollars.

On August 10, 1883 before a scheduled exhibition game, Cap Anson and his Chicago White Stockings had told Morton that his team would not play on the same field as the Walker brothers. Even though he had initially given Walker the day off due to injuries, Morton then re-inserted Moses in the game. He did this to force Anson to either play or lose his portion of the gate receipts. Anson decided to play that day, but when Chicago came to town the following year, they had already signed an agreement that the Walker brothers would not play.

To be clear, Morton isn’t exactly a villain here, either. Some 19th century racist comes to town with his National League team, and Morton and Toledo are in the minor league Union Association in 1883, so he bamboozles Anson — great! But he’s still basically an NPC (well, not really, he was a player-manager) handing a brief L to this main character of baseball racism.

In 1884, the Blue Stockings played their only year in the American Association (it wasn’t promotion/relegation, just more free-flowing alignments in baseball’s early days, Addy can tell you more after all that Ken Burns). Weldy — who is listed as Welday Walker in some places, but we’ll go with SABR here — was fresh out of college at Michigan and a reserve for Toledo. No sweat benching him, he’s already there. And Fleet was a catcher, the one position where a 19th century team would have depth, because of the necessity as they got hurt all the time. Morton could’ve made a stand, but it only would’ve hurt himself and the rest of his team — his teammates — including the Walker brothers, what with the team being run on such a shoestring that they were calling players’ brothers out of college to play for them — that they were the only team even willing to play Black players — defunct by 1886.

It was in 1887 that Anson really enshrined racism in baseball by refusing to play agianst Fleet Walker’s team in Newark, the Little Giants, who featured a Black battery of Walker and pitcher George Stovey. The big Giants, back in New York, had an eye on Stovey, and maybe he could have been the first of MLB’s Black Aces, but not in a league where the game’s most influential figure was racist even by 19th century standards. Let’s go to John R. Husman from SABR:

Cap Anson was not entirely responsible for baseball’s more than half-century of segregation, but he had a lot to do with it. The incident of August 10, 1883, in Toledo certainly brought the issue to the forefront and began an open, blatant, and successful effort to bar black players from Organized Baseball.

One of the obvious effects of institutional racism is all the greatness that never gets to emerge, because it’s held back. Cap Anson was a generational talent who helped set the game back about three-quarters of a century, from the Walker brothers to Pumpsie Green.

(That would’ve been a clever little ending had I gotten it together to post this episode on St. Patrick’s Day, which I did not, rather obviously. Sorry.)

And now, some Midjourney art that did not become the title of this episode:

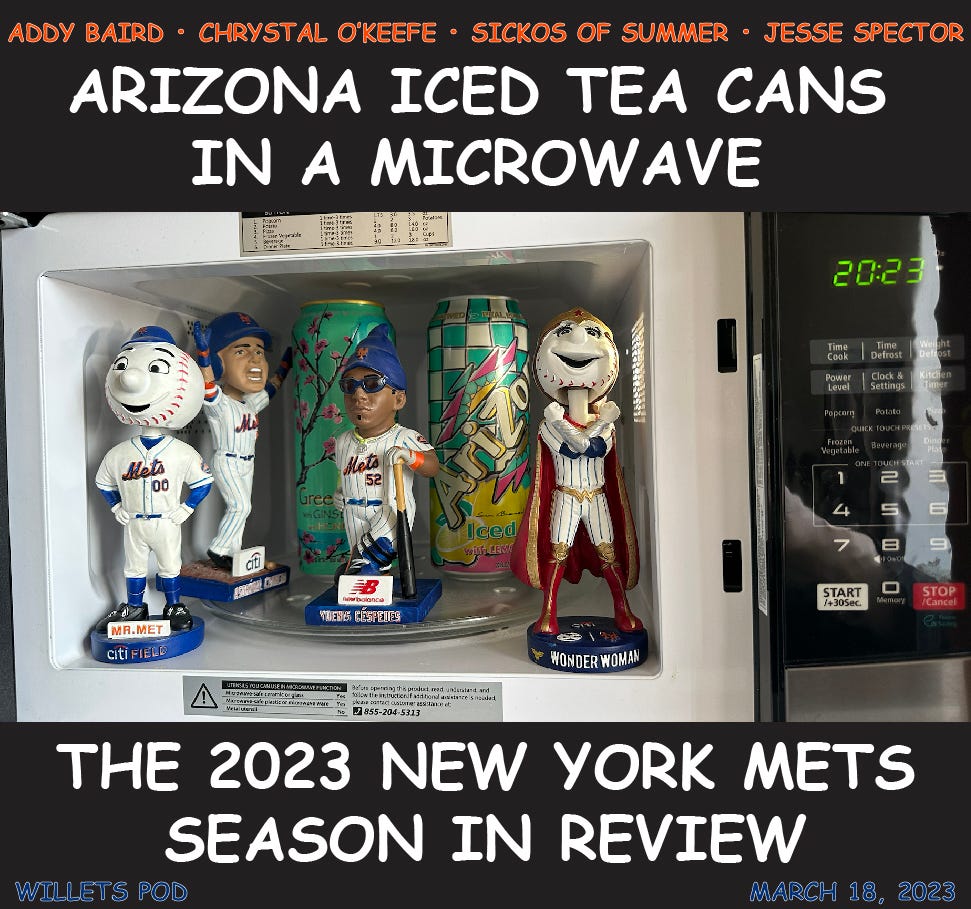

And now, the actual cover art for this episode… not made with Midjourney!

Share this post